Stefan

Latest posts by Stefan (see all)

- Making Every Marketing Dollar Count - March 31, 2025

- The Future-Ready PM: From Traditional Leader to AI-Native Strategist - March 27, 2025

- The Future of Product Management – Fireside Chat with Google PM Stefan F Schnabl - February 14, 2025

![]() When recently presenting to my engineering team at an all-hands, I put a simple slide on the screen showing two very old black-and-white pictures of a woman and a man. The audience listened up from their computers (it is pretty common for our eng teams to be on the computers during all-hands meetings) when I asked them: “Who knows the historical significance of these two people on the slide?” No one had an answer, as I had expected. Well, I started by telling them about Mary Ward, and Henry Bliss. Both have something in common: they are credited with being the first fatality from a traffic accident, Henry in the US, and Mary in Europe.

When recently presenting to my engineering team at an all-hands, I put a simple slide on the screen showing two very old black-and-white pictures of a woman and a man. The audience listened up from their computers (it is pretty common for our eng teams to be on the computers during all-hands meetings) when I asked them: “Who knows the historical significance of these two people on the slide?” No one had an answer, as I had expected. Well, I started by telling them about Mary Ward, and Henry Bliss. Both have something in common: they are credited with being the first fatality from a traffic accident, Henry in the US, and Mary in Europe.

![]() Henry Bliss got off the cable car in New York when an electric (!) car hit him in 1899 [1]. He dies the next day from his injuries. Mary Ward died from getting under the wheels of an experimental steam car in 1869 in Ireland [2]. While both of these instances are tragic, and their significance is somewhat hard to tie to future effects the car had on mankind, they did spark a unique perspective on the automotive: the one around car safety. Car safety, and the ability of a car to protect the driver and passengers in a crash, has since been an extremely important and emphasized component of car innovation, as well as car advertisement [3]. Car safety is a huge area of investment for the overall car industry, and a big discriminator for consumers [4]. Having a safe car is something that gives comfort beyond just the pure utility of being able to get from A to B.

Henry Bliss got off the cable car in New York when an electric (!) car hit him in 1899 [1]. He dies the next day from his injuries. Mary Ward died from getting under the wheels of an experimental steam car in 1869 in Ireland [2]. While both of these instances are tragic, and their significance is somewhat hard to tie to future effects the car had on mankind, they did spark a unique perspective on the automotive: the one around car safety. Car safety, and the ability of a car to protect the driver and passengers in a crash, has since been an extremely important and emphasized component of car innovation, as well as car advertisement [3]. Car safety is a huge area of investment for the overall car industry, and a big discriminator for consumers [4]. Having a safe car is something that gives comfort beyond just the pure utility of being able to get from A to B.

![]() Let’s go back to poor Mary and Henry. Did their deaths have an effect on the car industry? Well, you bet it did. Mary and Henry were just the initial signs for what was about to happen. With the mass penetration of cars in the 1930’s the death tolls kept rising and rising. It became a big problem to the car industry. While in many cases the product – the car – was not responsible for the accidents, the fatalities started tainting the perception of the car overall. Cars were considered dangerous and even evil [5]. Well, there were plenty of things wrong with driving at the time: no clear traffic regulation, no lights, no separation of traffic. However, people associated the result of the accidents with the main star of the show: the car. So what did the automotive industry do? Well, they did what every responsible product team does when their product starts killing a lot of people: run some tests to find out why. Testing a vehicle crash in 1900-1920 was not as straight forward as it might seem Today. Three main testing strategies were applied: Volunteer testing (some dud strapped to a rocket sled that was decelerated quickly), Animal testing (god, so cruel!), and Cadaver testing (gross) [6].

Let’s go back to poor Mary and Henry. Did their deaths have an effect on the car industry? Well, you bet it did. Mary and Henry were just the initial signs for what was about to happen. With the mass penetration of cars in the 1930’s the death tolls kept rising and rising. It became a big problem to the car industry. While in many cases the product – the car – was not responsible for the accidents, the fatalities started tainting the perception of the car overall. Cars were considered dangerous and even evil [5]. Well, there were plenty of things wrong with driving at the time: no clear traffic regulation, no lights, no separation of traffic. However, people associated the result of the accidents with the main star of the show: the car. So what did the automotive industry do? Well, they did what every responsible product team does when their product starts killing a lot of people: run some tests to find out why. Testing a vehicle crash in 1900-1920 was not as straight forward as it might seem Today. Three main testing strategies were applied: Volunteer testing (some dud strapped to a rocket sled that was decelerated quickly), Animal testing (god, so cruel!), and Cadaver testing (gross) [6].

Looking at a more detailed history of the CTD [7], it becomes pretty clear what the core characteristics of the application of the Crash Test Dummy in the automotive industry was: systematic repeatable product testing. Let’s repeat that for a minute: systematic repeatable product testing. Wow. Beautiful! If only every product development process would mature to a place where this is possible. Modern CTD’s are required to collect a minimum number of data for each application. This data is what can be exploited, and compared against data from previous crashes to draw conclusions on product effectiveness. Imagine you are trying to establish whether or now a new seatbelt material helps protecting the spine during a crash. Well, the CTD can answer this question. Not without investment (some cars will be crashed, for sure), but in a scientific and objective manner. It can be established under what conditions the new feature performs with what characteristics, and these conditions can be varied in a controlled way, and the outcome can be measured and compared. While testing is costly, making the wrong product call in the car industry can be even costlier [8].

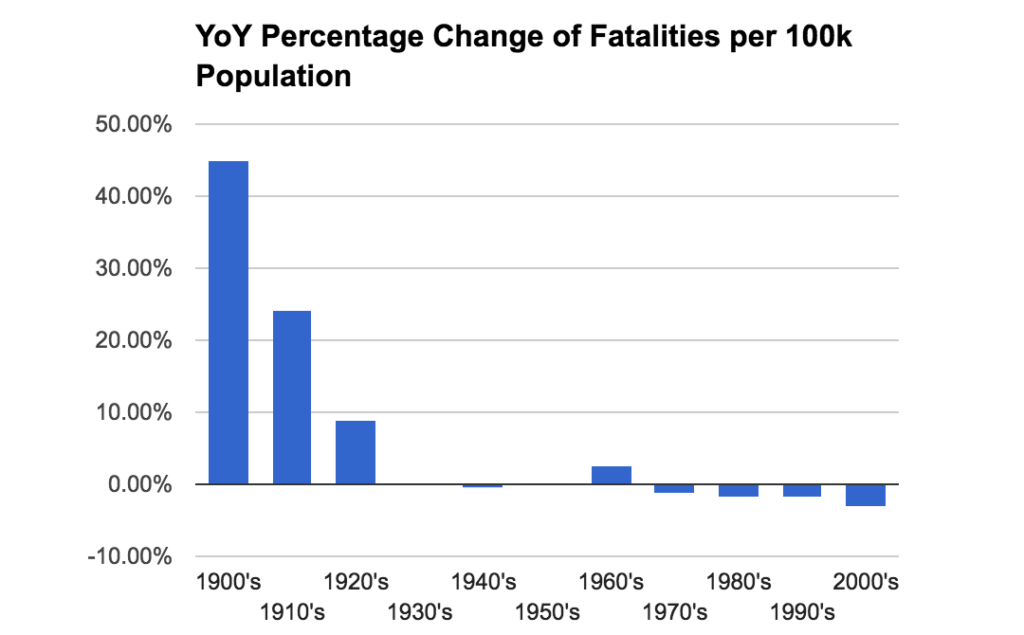

Verifying the causal influence of the CTD on car safety might be hard, a lot of things have been improved during the early 1900’s in terms of organizing and regulating traffic. All these measures (stop signs, traffic police, road separation) have had a tremendous impact on making cars and road traffic safer. Fatalities normalized by population are easy to find [9]. Looking at the average YoY growth in normalized fatalities, it can be seen that there was a fundamental shift after the 1930’s. However, there seems to be a sustained decrease in fatalities, and I want to think it is because the increased investment in measuring effects of car safety features.

Verifying the causal influence of the CTD on car safety might be hard, a lot of things have been improved during the early 1900’s in terms of organizing and regulating traffic. All these measures (stop signs, traffic police, road separation) have had a tremendous impact on making cars and road traffic safer. Fatalities normalized by population are easy to find [9]. Looking at the average YoY growth in normalized fatalities, it can be seen that there was a fundamental shift after the 1930’s. However, there seems to be a sustained decrease in fatalities, and I want to think it is because the increased investment in measuring effects of car safety features.